We delight in the beauty of the butterfly, but rarely admit the changes it has gone through to achieve that beauty.

Maya Angelou

Visual art is a clever seducer; a few well-placed brushstrokes or a thoughtfully-composed photograph are enough to evoke stories far beyond the image. Kadir Nelson, an artist whose work has graced the covers of Rolling Stone and The New Yorker, paints his subjects with warmth and nuance which invite the viewer to ponder their interior lives more closely.

One could imagine comic-style speech bubbles added to “Art Connoisseurs,” a riff on a 1962 Norman Rockwell painting updated for 2019. The distance between the contemporary Black couple in Nelson’s work and the street art they observe may well resemble that between Rockwell’s gray-suited gallery guest and the Pollockesque piece before him — however close or far that may be, in either case.

I think art is most effective when it stirs something up inside of people. The work that I create, I intend for it to remind people of the better parts of themselves, because I feel that if you see something that reminds you of something that is beautiful about yourself, or Integris, or something that is that reminds you of your inner strength and pushes you to move in that direction, then I think that I’ve kind of I’ve done my job as an artist to, to, you know, for that purpose.

Kadir Nelson [source]

As a years-long fan of Nelson’s thoughtful work, I was drawn back to his portfolio when considering art inspiration for my custom Black History Month manicure. (Victoria at Bed of Nails NYC hooked me up, watch her in action!)

“Spring Blossoms,” the painting on the cover of the latter February 2019 New Yorker issue, portrays an elegant woman dressed to the nines, seated as if a guest at the theater or the symphony, a delicately wrought silver lorgnette in hand.

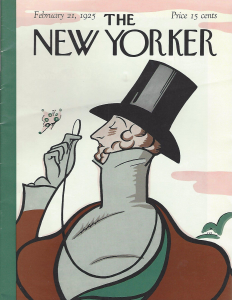

Elements of the piece – the wallpaper’s butterflies, the subject’s pose in profile holding spectacles aloft – allude to the New Yorker‘s longtime mascot Eustace Tilley, the top-hatted dandy who debuted on the publication’s February 21, 1925 first issue.

Tilley’s man-about-town has since been reimagined numerous times for subsequent anniversary issues, including by Nelson himself, but “Spring Blossoms” evoked for me my childhood-cultivated admiration of sophisticated African American ladies of leisure.

The subject peers through her glasses with a gentle and discerning gaze, pulling her sumptuous stole about her shoulders, flickers of amusement gracing the corners of her mouth. (I appreciate her dual lenses, in contrast to Tilley’s monocle – they tell of her relative enthusiasm to take in what’s there to see, contrasting with the dandy’s indifferent observation.) She brings to my mind memories of trips with my mother and sister to watch the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, where the actual performance was preceded by the runway of stylish attendees queuing outside. My childhood education in arts appreciation extended to the pages of my mother’s vast collection of African American periodicals – Essence, Ebony, Jet – and I learned that attending community cultural events meant the chance to see such glamour in person.

Although I am first-generation American and the offspring of immigrant parents, my mother taught US history for years in a predominantly-Black school district, and her newcomer’s perspective to the material translated into an enthusiasm to share what she learned with my older sister and me. Her influence was significant enough that my sister elected African American studies as one of her undergraduate majors; to this day, two of my enduring memories of Ntozake Shange’s work are of my family attending the theatrical adaptation of Betsey Brown, and of seeing For Colored Girls at a campus staging organized by the Black Student Union (for which my sister served as vice president).

Thanks to my suburban New Jersey hometown’s proximity to Broadway – enough to see multiple shows each year, even if on the occasional standing room ticket – I grew up watching the Tonys avidly, hoping to trace a line between the announced winners and my collection of Playbills. My heroes were Audra McDonald and Anika Noni Rose, LaChanze and Lillias White. I’m not too proud to say that I cried when Patina Miller won her Tony for Pippin, then spilled waterworks years later watching her perform live at Cafe Carlyle. She, as well as the others listed, is possessed of transcendent talent, burnished with years of effort, and I feel fortunate that I was raised to hold the work of artists like her with such high regard.

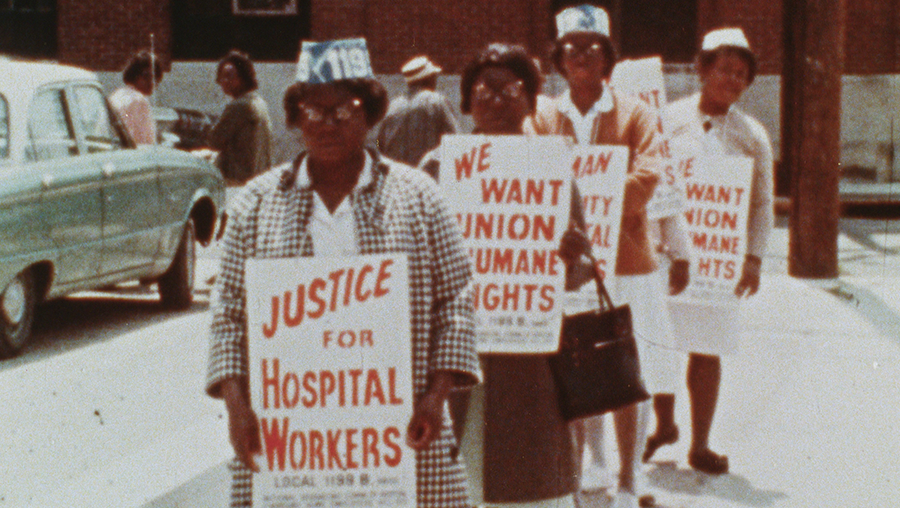

The “Spring Blossoms” subject is both an observer of and herself a work of art, characterized by self-possession, a welcome image given the real-world demand for Black women’s labor. I recently watched the 1970 documentary I Am Somebody, screened as part of BAM’s film series on the Black worker.

Leaving the theater, I was impressed by the women’s persistence in the face of administrative disregard and police violence, while also reminded of Audre Lorde’s book of essays A Burst of Light, from which originates one of her better-known quotations:

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”

I considered a Simone Leigh exhibition I’d attended back in December, where intricate repeating elements on several sculptures called attention to the tedium involved in production.

Finally, I remembered words from Alice Walker, who as much as spelled it out in one of her books: “resistance is the secret of joy.” The woman of “Spring Blossoms” is an image of serenity; her peace and pleasure exist in quiet defiance where imposition on Black women’s time, energy, labor, and intellectual property is a societal norm.

In the spirit of Walker’s quotation, I’m sharing some of Lauren Silberman’s portraits of the Long Nail Goddesses of Newark; the group members’ authenticity and joy in sisterhood shines through, whether in still images or video.

I find it apt that Black History Month immediately precedes Women’s History Month in the United States; observed thoughtfully, two straight months seems a better fit to properly honor the depth of African American women’s historical contributions. My manicure wouldn’t be on point if it weren’t paying an appropriately lasting homage, and I’m happy to remember that gratitude each time I look down at my hands.